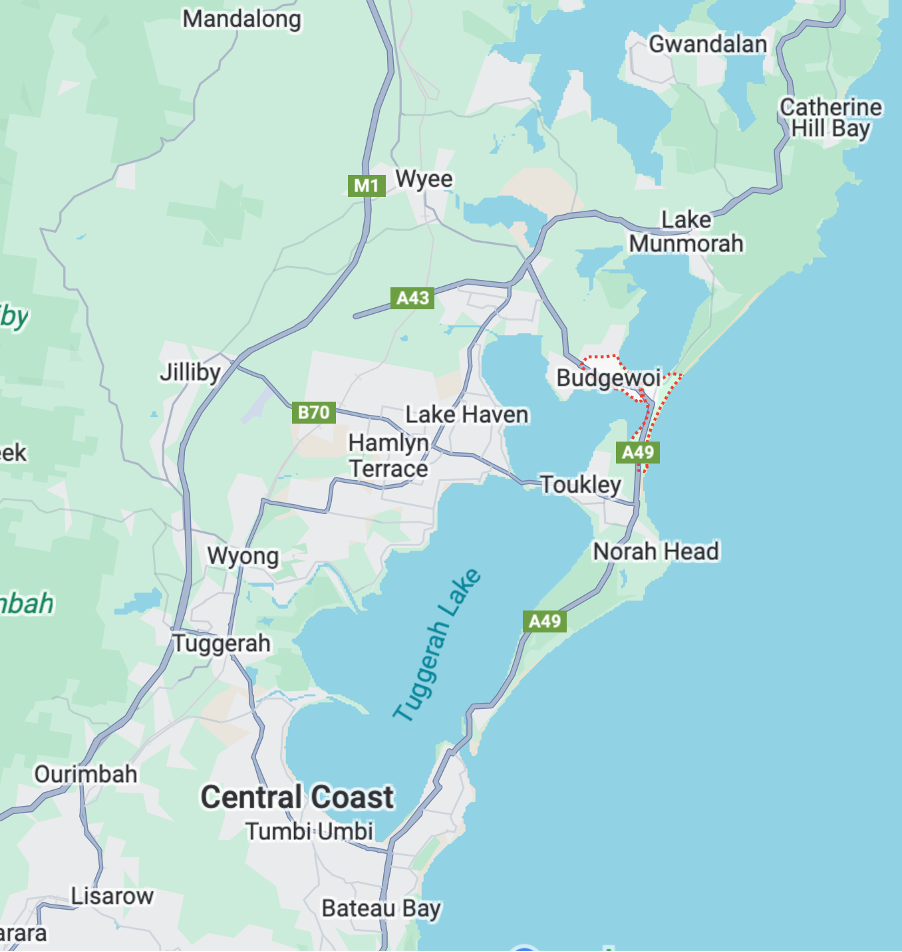

Back in, I don’t know when, while I was living on the Central Coast of NSW, we took the scenic route home along the beach through Budgewoi, and I spotted a cheap sign advertising “PRIVATE INVESTIGATOR” in white letters on black paint, with a mobile number listed below it.

I don’t remember which town. If I could find the place again, I’d take a picture of that sign and use it as a cover. Maybe all my covers for this series of books.

But I wondered—what the hell would a PI do for work in a small town of 3,000? Definitely nothing undercover. After a short time, he’d know all the town’s secrets, as well as those of the surrounding towns.

And thus was born Malcolm Durridge, a former NSW Police Senior Sergeant who left the force under mysterious circumstances. (Perhaps something for a future book. Perhaps.) He now operates a one-man PI shop above a TAB betting establishment in a small, fake town on Tuggerah Lake.

Mac’s cases vary from bank fraud and international conspiracies to a 13-year-old kid paying him $25 to find his stolen coin collection.

He got an old attorney friend whose help he frequently needs, an ex-wife (who is well on her way to becoming a doctor) and Barry (Baz), an indeterminately aged man who chooses to live homeless. Baz serves as his invisible (to the rest of society) source, keeping an eye on things when things need an eye or two.

E-books can be found on Amazon here, with more e-retailers coming soon.

Paperbacks (including Large Print) are on Barnes & Noble: Mac D | A Step Too Far | Hunter/Prey and other good and evil bookstores.

Subscribe (at the top right of this page) to be notified when the next in the series, Fast Track (18 July), is available for pre-order.