I bang on this a lot, and if the truth be told, this is only a minor component of a good story, but one most often missing.

Stories have a structure. Generally, three acts. There are other structures, but they all resolve, in one way or another, to three acts. There are certain things a reader (or viewer, for movies and television) expects in Act 1. There are things readers and viewers will absolutely not accept in act three. And there are ways a story transitions from one Act to another that make the story more satisfying.

I’ve posted this before on previous incarnations of this or other blogs. I will do it again because I truly believe this is one of the crucial — and amazingly simple — ingredients to stories. I apologise in advance if learning about this ruins stories for you henceforth. You will recognise the end of the first Act and the move into the meat of the second Act. You will see the midpoint turn and feel the all-is-lost moment at the end of Act Two.

But that shouldn’t kill your enjoyment. It adds a layer of entertainment to good books and movies.

If you’re a writer and learning this for the first time, welcome. And recognise that once you know this, you can “forget” it. It will be the scaffolding upon which you hang your story. The real creativity comes in the bits between the plot points.

If you’re of the crowd who firmly believes that acknowledging such a structure exists and that following it will produce cookie-cutter, unimaginative and limp stories, I can only point you to “Witness”, “Breaking Bad” and “The Edge of Tomorrow”, all excellent, inventive and all following this structure. Pretty much every successful novel and movie over the past half dozen decades follow this three-act structure.

A high-level view first, then as the weeks progress, a post for each of the important bits.

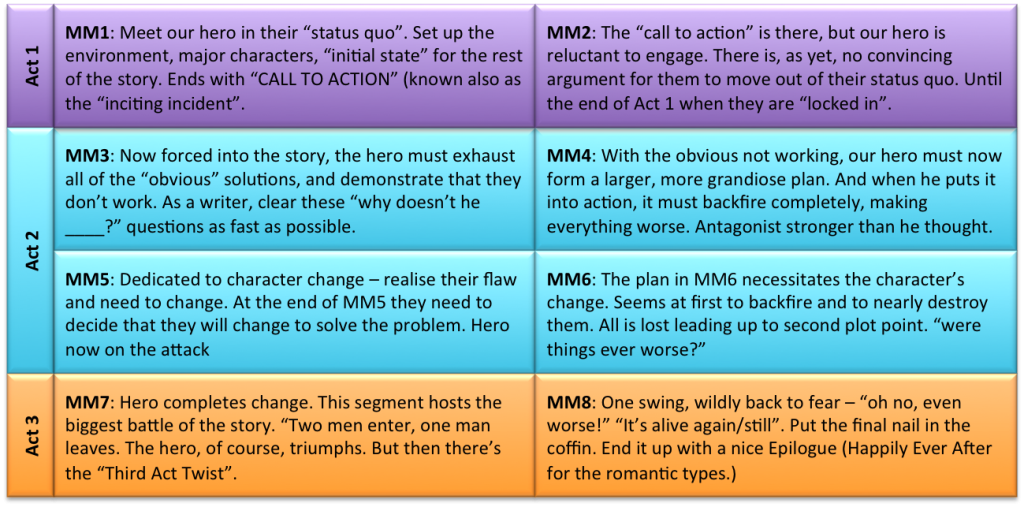

As mentioned above, a story is divided into three Acts.

Acts are separated by the First Plot Point (between Acts 1 and 2) and the Second Plot Point (between Acts 2 and 3).

A note on terminology. Some call the first plot point the “inciting incident”, and that’s fine — this isn’t calculus — but for clarity going forward, I don’t.

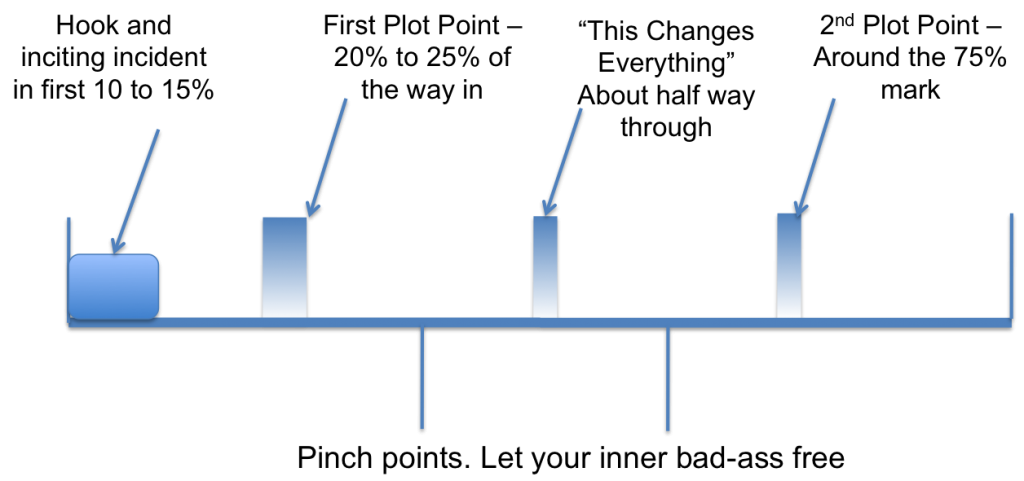

The Inciting Incident in this model (not my model — it’s been around long before I started writing) occurs in the first 10% to 15% of the story. It’s the thing / event / whatever that triggers what will eventually be the first plot point at the end of Act 1. Like if a box of dynamite explodes to trigger the end of Act 1 and the start of Act 2, the inciting incident is lighting the fuse. Or, in one of my books — G’Day LA — the inciting incident is our protagonist Ellie Bourke discovering her friend and roommate has died, which convinces her to abandon her fledgling acting career and return to Australia. The First Plot Point is Ellie’s realisation that it wasn’t suicide, as the police believe, but a murder. She then abandons her return home to find the killer.

Can’t forget the Hook. Earlier in the story, the better. If you can hook the reader/viewer in the first page/scene, so much better.

In my current WIP, the opening pages have Dan McGinnis, owner of McGinnis Investigations, arriving at the office one Monday morning to find his surveillance expert passed out in a pool of blood in the office kitchen. This drives the rest of the story.

In Act 1, the status quo is defined. What are the protagonist and antagonist doing in their daily lives? What elements of their lives would be put most at risk by taking up whatever the First Plot Point brings them? If at all possible, any characters involved in the Act 3 resolution (which we will get to) should be mentioned, even if in passing, in Act 1.

Now, remember that Act 2 represents the protagonist stepping into what is the meat of the story. The First Plot Point pushes the protagonist out of their status quo into “the story”. You can’t just have the main character say, “okay, let’s go do this,” and expect your reader / viewer to merrily go along for the ride. There should be resistance in Act 1. Resistance to taking that step. Something should hold the protag from launching into the story. So you need something at the end of Act 1 that triggers this launch.

This “something” is the First Plot Point. In G’Day LA, it was the fact that her roommate had booked a career-changing gig, something he’d been dreaming of for years, for the afternoon of his apparent suicide. She then knew she had to do something about it.

Act 2 is generally split into two halves. It takes up roughly 50% of the story pages / viewing time, and this is where the meat of the story unfolds. Obviously, there needs to be an arc through this. The protagonist needs to work through real and fake clues in crime fiction. In romance, the couple must learn about each other, faults and all. I will focus on crime fiction because that’s what I write, but the principles are non-genre specific.

The first half of Act 2 should be an envelope of fog. Get the obvious solutions to the problem out of the way first. Why don’t they go to the cops? The cops have already made up their minds. How are you sure it wasn’t a suicide? The victim’s agent had confirmed attendance on the show just before the alleged suicide.

In the middle of this first half of Act 2, throw in a scene to demonstrate the abject evil of the antagonist. It’s not necessary for the protagonist to know of this evil at this time, it’s enough to show the reader. This is called the First Pinch Point.

But if the protagonist sees it also, so much the better.

Once the obvious has been put to bed, the MC starts down a path that seems like the right thing to do. Maybe based on misinterpreted facts, maybe based on fake facts. But they are invested in their path until

WHAM

they stumble across the “this changes everything” Midpoint. This keeps Act 2 alive. It’s a long Act. A full hour in a two-hour movie. Two hundred pages in a standard novel. The midpoint twist needs to be a logical extension of what has already been explored (and possibly mistakenly discarded). No out-of-the-blue surprises. What it does for your story is restart the investigation. Old clues can be revisited with a different eye. New clues can be brought to light. It’s a whole new story. Sort of.

Much more progress is made, and about halfway through the second half of Act 2, mirroring the First Pinch Point is the Second Pinch Point. It provides a similar purpose as the first but can also be used to show the depths the protagonist will go to defeat the baddie. Embrace it.

It’s not all easy, though. The end of Act 2 plays best when the protagonist is at their lowest, seemingly defeated with nowhere to go. The All is lost moment. This is when the final piece of information gives the hero the path to victory. This final piece of information is The Second Plot Point. And what follows is:

Act 3. This starts with the battle of all battles. Two women enter, and one leaves kind of battle. The kind of battle that, at the end, with the protagonist victorious, seems like it’s over. But there’s one final twist. The “it’s still alive” moment. One final nail left for the coffin. It is a hard slog to the finish with as many relevant obstacles as possible.

When it’s time for the happy ever after (if you’re going that way), it works really well if your final scene mirrors your opening scene as much as possible.

And you’re finished.

Some admonitions:

- Your hero needs to be a hero. Don’t have them rescued unless that rescue is 100% driven by something the hero has already provided.

- Don’t add characters, skills, weapons, or anything in Act 3 that drives the conclusion. I read a book recently where the main character threw a fastball with unerring accuracy at a bad guy, hitting him in the head and knocking him out just before he attacked. The fact that he played baseball in college wasn’t revealed until AFTER that throw. That’s cheating. Introduce the baseball career in casual conversation in Act 1.

- Make sure your transition scenes flow smoothly with scenes that lead up to and out of them. The First Plot Point can’t drop from the sky any more than expertise in baseball can.

- No fucking cliffhangers. Finish the story. Resolve all threads introduced in the first two Acts. If you want to set up a sequel, fine, but finish the story you started.

If you have any comments, questions, or disagreements, please let me know below.