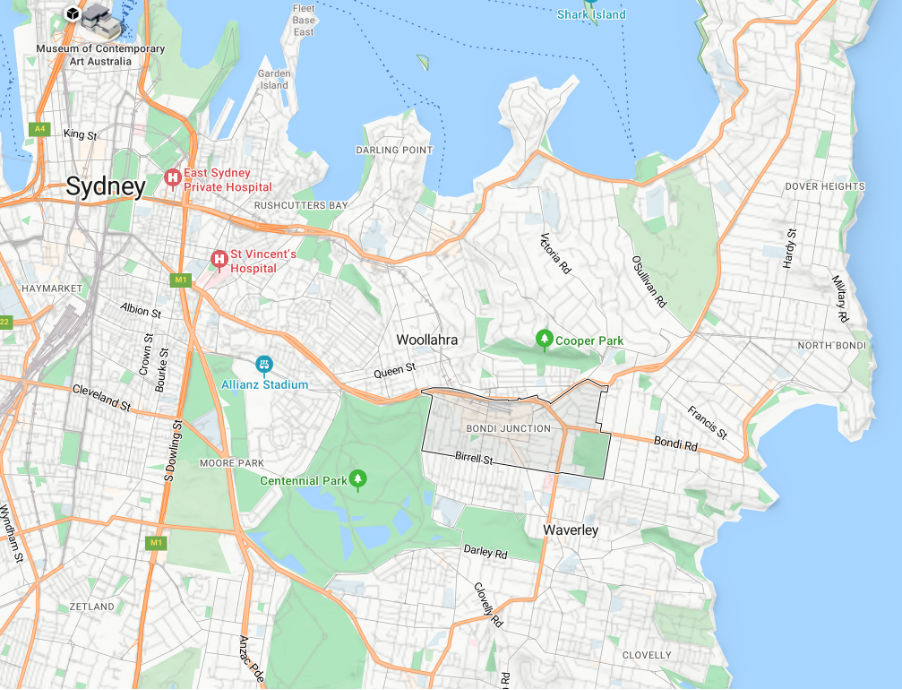

I’m in the middle (literally) of the first draft of my next Nick Harding book. I don’t have a title yet. The premise is pretty straightforward: The story opens with Nick regaining consciousness in a barn somewhere in rural suburban Sydney. He’s been whacked on the head. He can tell by the painful lump on the back of his skull and the low-grade, behind-the-eyes headache he’s sporting.

He’s got no recollection of what happened or where he was when it did happen.

Davie and Lucy, worried about his disappearance, are on their own hunt to track him down, encountering a special group of people trying to stop them. People they’ve never met before.

Odd-numbered chapters are first-person, Nick’s POV, and his efforts to get through the mess. Even-numbered chapters are third-person, POV of whatever characters I need to drive the rest of the story. Mostly Davie and Lucy, but as the story unfolds, more are added to the tale.

Right now, I’m at the midpoint of the first draft. My favourite part of both the plotting and writing process. If I do my job well, I’ve led you down a path where you think you know what’s going on, where you start having a shade of an inkling of a possible ending.

Then I give you the midpoint, and you hurt your back changing direction.

I think this one has a good midpoint. Thought about how to set it up for months.

And even though I’ve warned you, when you read the final product, it’ll still make your brain lose traction on the turn.

Sometime in July or August, the Nick Harding book I haven’t named yet will be ready to ride.

Subscribe (top right of this page) to get notifications of both pre-order and ARC opportunities.

Leave a Reply